As obras e os dias

Solo show | Pivô Arte e Pesquisa | São Paulo, Brazil | September 28 > October 30 2017 | Curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti

Works and days | Jacopo Crivelli Visconti

In recent years, Marco Maria Zanin has been developing his work within two diametrically opposing contexts, which carry a profound symbiotic relation between each other. The first context – also from a biographical point of view – is the rural landscape of Veneto, the region in Northern Italy where the artist’s family originates from and where his oldest childhood memories lay, many of them linked to ancient rituals and traditions, in which the beliefs, knowledge and needs of agriculture are indissolubly intertwined. The second is the city of São Paulo, where Zanin has spent long periods of time, fascinated by the megalopolis’ totally distinct temporality, with its pathological vocation towards the future, which makes it a hostage to a chronic lack of knowledge about its own past. By placing himself – both conceptually and physically – on the edge of these two worlds, the artist witnesses and reveals the clash of two world visions that are radically distinct and apparently irreconcilable, but that coexist despite all and, mainly, despite the common places on contemporaneity. In his classic Hybrid Cultures (1990), Argentinian anthropologist Nestor García Canclini proposes “strategies for entering and leaving modernity”. Zanin’s artworks highlight the need to “leave” a superficial vision of contemporaneity so it can be understood in a deeper and more comprehensive way.

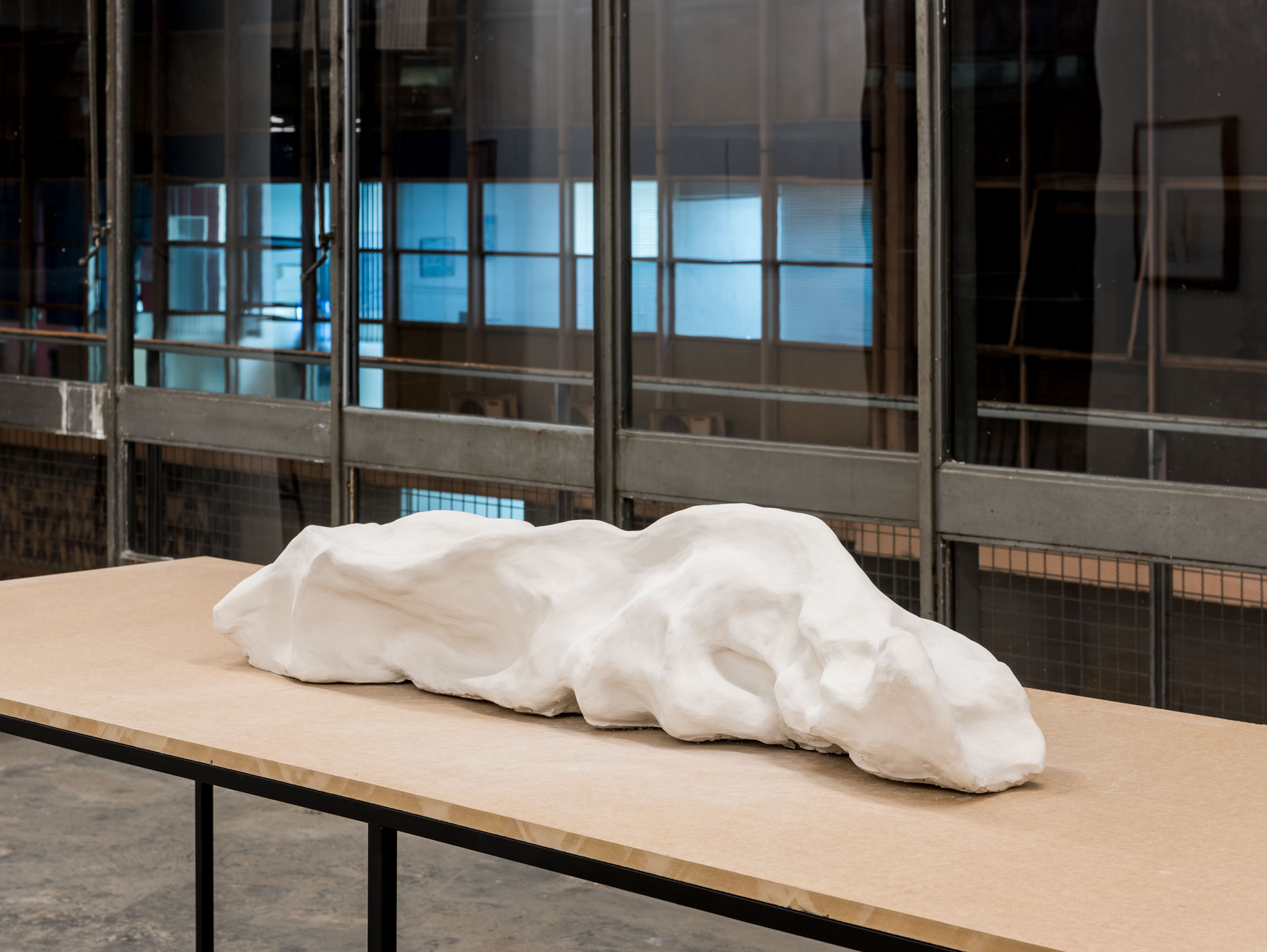

A fundamental reference in the conception of several of the artworks in this exhibition is Georges Didi-Huberman, who considers debris and ruins almost as symptoms, that is, signs of something distinct, in this case, a different time from what we perceived at first sight. The reference is fundamental to understanding the series of small porcelain sculptures that constitute Restituição, in which rubble from construction and refurbishment sites, which the artist collected from skips in the city centre, are patiently ‘portrayed’ in an almost infinite cluster of sculptures. In the artist’s own words: “In both literal and metaphorical ways, the modus operandi requires me to kneel down in order to observe and collect leftovers from the hurricane of modernity. In other words, an overflowing of our own humanity beyond the tracks of capitalism, searching for the construction of a meaning, of a path. Of a horizon at the end of the world”. Once collected, the original rubble is not used as moulds, but reproduced freehand, in an attempt to condense them and return their power. In a world in which it is possible to conceive that all existing images and information are stored somewhere, the decision to oppose this immense memory with modest and precarious sculptures – apparently bound to the same process of dissolution and oblivion to which the remains of construction sites produced by the city are endlessly destined – becomes symbolic and meaningful.

In general terms, if we consider, for example, that the planes in Ferite feritoie are also ruins or ‘leftovers’ of a time, of a type of knowledge and practice that fades in front of our eyes, Didi-Huberman’s analysis is central to the exhibition as a whole and not only as far as Restituição is concerned. In Ferite feritoie, the artist collected several planes similar to the ones his grandfather used for carpentry, which directly refer to the history and tradition of a kind of artisanal knowledge that was once almost universal but that has today become restricted to a professional context. Subsequently, the planes were cut and sectioned, and the resulting forms are reminiscent of African or Pre-Colombian masks and idols. The encounter with this archetypal form, previous to the civilisation that we call Western, is not accidental but emerges from the understanding of the need to invoke all these references, pillars or debris that underpin our ruins, paraphrasing the T.S. Eliot’s classic verse in The Waste Land (1922): “These fragments I have shored against my ruins”. As well as conjuring – almost per forza di levare as Michelangelo would say – the imprisoned form in the artisanal tool, the cut plays the symbolic role of highlighting the clash between two times: the time of long years, decades or even centuries of use that gradually wears the instrument down, and the time of the quick and precise cut, the mark of a contemporaneity that, almost paradoxically, retrieves innate and original memories. In this sense, the photos of Ferite feritoie, can be considered ‘fragments’ of a reflection on time or rather ‘times’: the time of seasons and climate changes that have guided and regulated life and agriculture since Hesiod (whose poem, from the 8th century BC, lends the title to the exhibition), and the time of uninterrupted coexistence, through overlapping and simultaneous layers, that seems to mark our daily existence, where the gap between novelty and obsolescence is increasingly narrower.

The artist’s position within this friction is not explicit. The ambiguity is revealed, for example, by the images of the series Lacuna e equilíbrio, in which the debris that results from the frenetic pace of construction and destruction in São Paulo is transposed into an atemporal context, inspired by the paintings of Giorgio Morandi. Despite the suspended and metaphysical atmosphere of the Bolognese painter’s images, light is almost tangible, sculpting the contour of the few objects carefully displayed on a small table. The importance of light and the attention to its transformations throughout the day and the year reveal a proximity between both artists that go beyond the iconographic reference, as it becomes evident, amongst other examples, in the diptych Maggese, a record of the movement of sun light in the artist’s studio. Maggese was an agricultural practice that consisted of letting a field rest for a month (the month of May, maggio, in Italian) so it could recover after harvest before being cultivated again. Here, by crossing through the ajar window, the light draws a shape on the floor, which the artist fills in with soil, creating a small ephemeral sculpture, whose transience is immediately revealed by the moving light itself. Perhaps, it is precisely in the impossibility of defining the moment of rest that resides the key to understanding this piece and, in general terms, Marco Maria Zanin’s poetics: there is no single moment that is more important than the other, in the same way as there is no decisive moment. Everything is in flux but each instant of this interminable flux defines us forever.